Effects of forces

Forces can do various things to an object. They can:

- Change the shape of an object

- Accelerate an object

The different effects of forces will be discussed in this chapter

Effect of forces on a spring

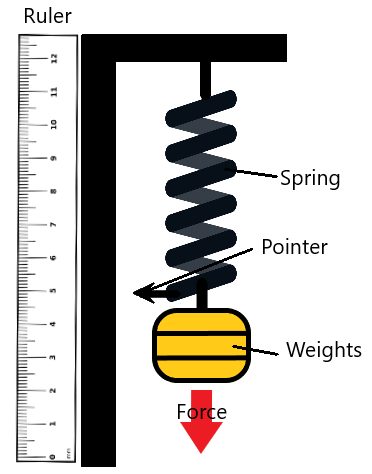

When a load is hung off a spring, the spring will extend. The extension of the spring varies with force. An experiment can be done to demonstrate this.

The downward force on the spring caused by the load is what makes the spring change shape

The experimental procedure is as follows:

- Measure the unloaded original length (OL) of the spring (to the nearest mm) by using the pointer and the ruler

- Add a 100g mass at the end of the spring and measure the new length (L1)

- Calculate ‘extension‘ by calculating the change in length of spring (L1-L0)

- Repeat the process 6 times, adding an extra 100g mass each time

- Plot a graph of extension against force, where force = mass X 10 N/Kg

For instance: Measure the first length with no mass (L0). Then add the first 100g mass (mass 1) and measure the new length (L1). The ‘extension’ of the spring after adding mass 1 is the change in length of the spring (i.e. L1-L0). Then add another 100g to make it 200g in total (mass 2). Measure the new length of the spring (L2), and the extension (L2-L0). Repeat this process at least 6 times.

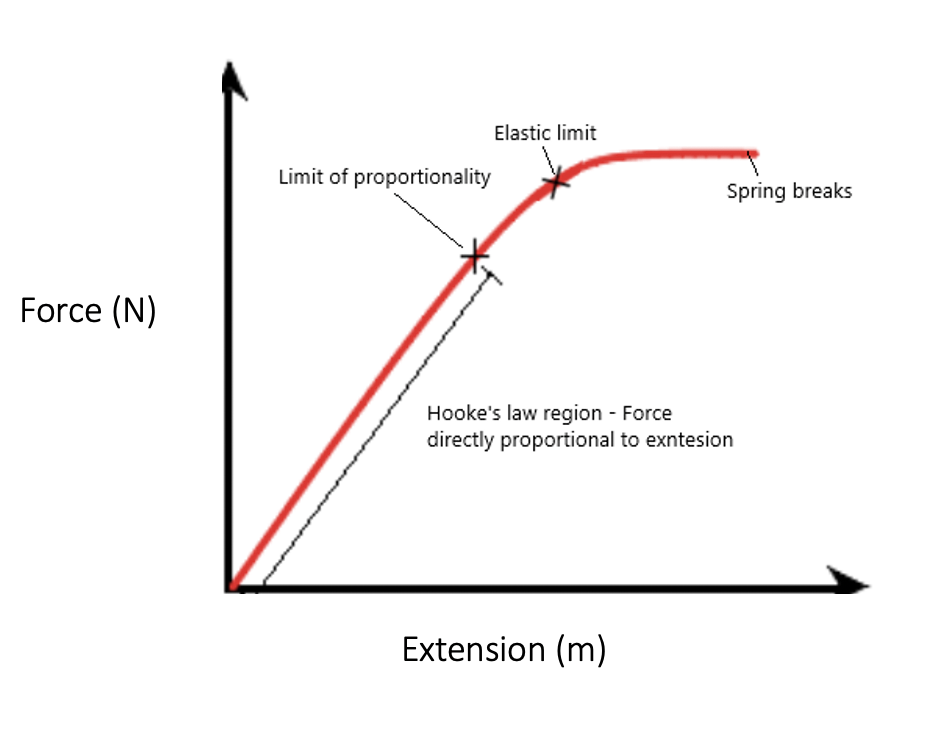

The extension-load graph should look like this:

Important concepts about this graph are:

- Spring extension is directly proportional to the force applied until the limit of proportionality is reached (this is the hooke’s law)

- Further force on the spring causes extension that is non-proportional to the force applied. If the force is removed, the spring will return to its original length/shape

- After the elastic limit, the spring cannot return to its original length even after the force is removed

- Eventually the force may be too great and the spring breaks

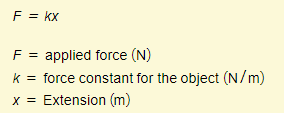

The hooke’s law states that the extension of a spring is directly proportional to the force applied (given that the limit of proportionality or the elastic limit is not reached).

Force, mass and acceleration

Understanding the formula

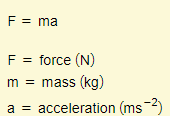

Not only can forces change the shape of an object, it can also accelerate it.

The equation is as follows:

- The larger the force, the greater the acceleration of the object (as long as the mass stays constant)

- The larger the mass, the smaller the acceleration as long as the force stays constant

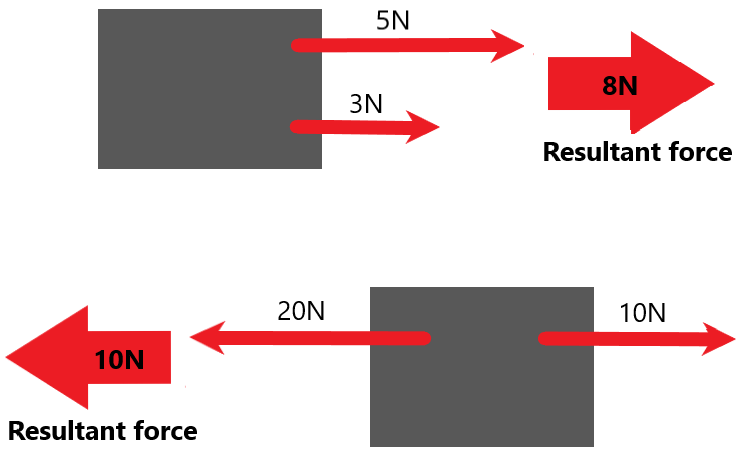

Resultant force

Forces always act in a particular direction. They are a vector quantity (just like velocity).

Therefore the resultant force on an object is the overall force when the size and direction of all forces acting are taken into account.

- Forces in the same direction are added together

- Forces in the opposite direction are subtracted

Centripetal force

The centripetal force is the force that causes an object to move in a circle. This force always acts at a right angle to the direction that the object is travelling, which causes it to move in a circle.

The force acts at a right angle to the direction that the object is travelling. The force does not do any work on the object because the object does not move in the direction of the force.

The force constantly changes the direction of the object without changing it’s speed. This means that velocity is constantly changing, and the object accelerates towards the center of the circle/orbit.

Remember, velocity and acceleration are both vector quantities. Even if the speed of an object is not changing, if the direction is changing then the velocity is changing. And if the velocity is changing, then the object is accelerating.

The centripetal force increases if:

- The mass of the object increases

- The speed of the object increases

- The radius of the circle decreases

If the centripetal force is suddenly removed, then the object will move on a tangent to the original circle.

Friction and air resistance

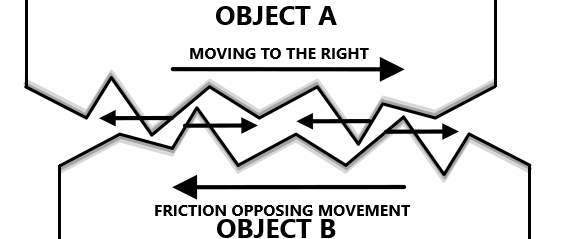

Friction is a force between two surfaces which impedes motion and results in heating. It is the resistance that one surface or object encounters when moving over another surface/object.

At a microscopic level, object surfaces are not 100% smooth. They are rough and uneven, and therefore when moving one object over another, friction will always oppose that movement.

Air resistance is a form of friction. When free falling in the air, the air molecules will collide against the falling object and create an upwards force which opposes the downwards force of the object.

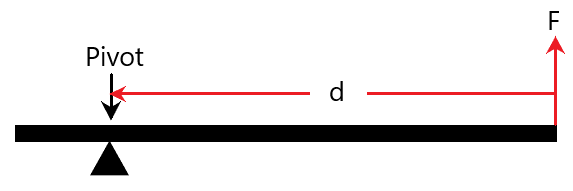

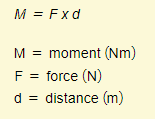

Turning effect

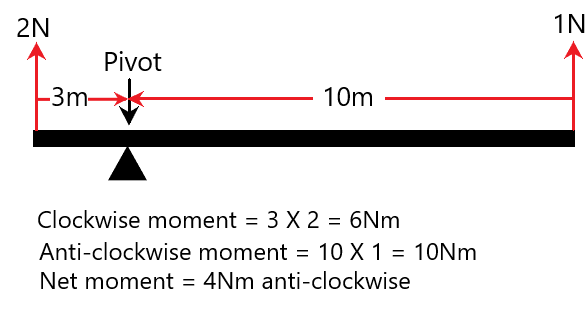

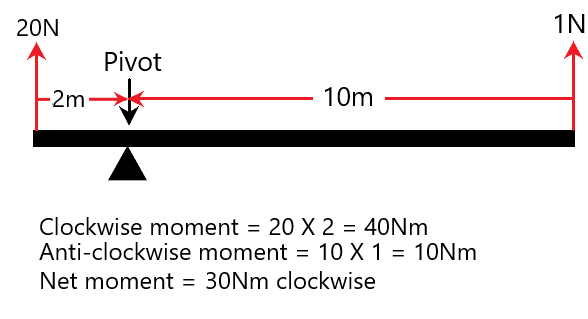

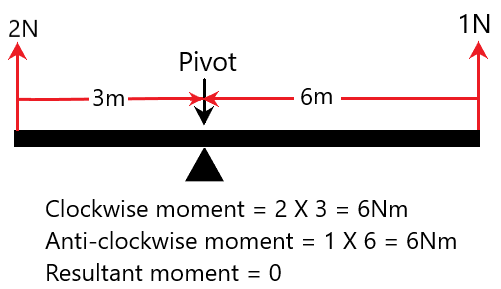

The turning effect or moment of a force about a pivot is equal to the force multiplied by its perpendicular distance from the pivot.

If an object is in equilibrium, it means that there is no resultant turning effect and no resultant force.

To calculate the resultant moment, you must calculate two things:

- Clockwise moment

- Anti-clockwise moment

If the clockwise moment is greater than the anti-clockwise moment, then the object will turn clockwise. Whichever direction has the greatest moment, the object will turn in that direction.

If the clockwise moment = anti-clockwise moment, then they will cancel out. The object is in equilibrium and will thus not turn.

The resultant moment causes anti-clockwise rotation

The resultant moment causes clockwise rotation

There is no resultant moment, so the object is in equilibrium

An experiment can be conducted to demonstrate that there is no net moment on an object in equilibrium:

- Anticlockwise moment due to 9N weight = 9 X 0.4 = 3.6Nm

- Clockwise moment due to force of spring balance = 12 X 0.3 = 3.6Nm

- Conclusion: The ruler is not rotating, it is in equilibrium because clockwise moment = anticlockwise moment

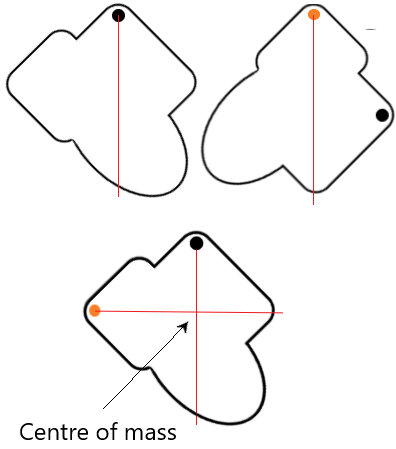

Centre of mass

The centre of mass of an object is the point on the object where the mass can be considered ‘concentrated’ and hence where the weight of the object is considered to act.

The centre of mass of a plane lamina can be determined by using a simple experiment:

- Push a pin through a point anywhere on the edge of the lamina, and allow it to swing freely

- Once the lamina is hanging still, mark a vertical line downwards from the pin

- Take out the pin and push it through a second point on the edge

- Again, allow the lamina to swing freely and come to a stop

- Mark another vertical line downwards from the 2nd pin

- The point at which these two lines cross is the centre of mass

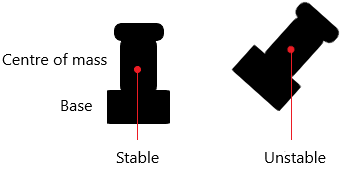

The centre of mass affects the stability of an object.

- An object is stable if it’s weight (the force acting on the centre of mass) is inside the base of the object.

- An object will tip over if it’s weight is outside the base of the object

Therefore a low centre of mass and a large base increases the stability of an object.

A high centre of mass and a small base decreases the stability of an object.

Vectors and scalars

There are key differences between scalar and vector quantities that you must be aware of:

- A scalar quantities have magnitude only such as: mass, time, speed, energy

- Vector quantities have magnitude and direction such as: velocity, acceleration, force

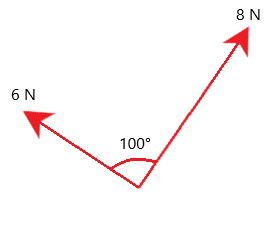

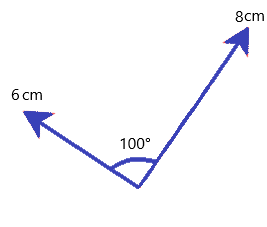

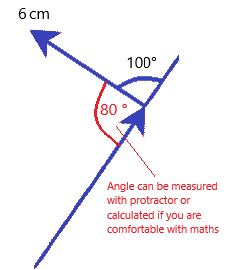

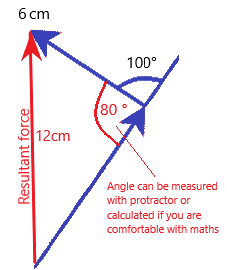

With the combination of two vector quantities, we can graphically determine the resultant (overall) vector using a scale diagram.

For example, use a scale diagram to calculate the resultant force in this diagram:

- Choose a scale i.e. we will use 1N = 1cm

- On paper, re-draw the diagram with the appropriate scaled lengths

- Arrange the forces ‘nose to tail’ so that the arrows follow on

- Draw the resultant force in the direction of the arrows, and measure it’s length

- Since 1cm = 1 N in our scale, 12cm = 12N resultant force